A new post in praise of students who resist pressures to identify with existing categories of career, calling and more, hosted by VocationMatters, a site of the Network on Vocation in Undergraduate Education.

Dispatch from Warsaw

A blog post on the resurgence of fascism. For the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Religion and Ethics site.

The Paradox of Wu-wei

A review discussion of Edward Slingerland’s Trying Not to Try: The Art and Science of Spontaneity and larger issues of well being.

The Road Ahead

Delivered at Maryville College on 4 February, 2020

Malachi 3:1-4

See, I am sending my messenger to prepare the way before me, and the Lord whom you seek will suddenly come to his temple. The messenger of the covenant in whom you delight–indeed, he is coming, says the LORD of hosts. But who can endure the day of his coming, and who can stand when he appears? For he is like a refiner’s fire and like fullers’ soap; he will sit as a refiner and purifier of silver, and he will purify the descendants of Levi and refine them like gold and silver, until they present offerings to the LORD in righteousness. Then the offering of Judah and Jerusalem will be pleasing to the LORD as in the days of old and as in former years.

Luke 2:22-40

2:22 When the time came for their purification according to the law of Moses, they brought him up to Jerusalem to present him to the Lord 23 (as it is written in the law of the Lord, “Every firstborn male shall be designated as holy to the Lord”), 24 and they offered a sacrifice according to what is stated in the law of the Lord, “a pair of turtledoves or two young pigeons.”

25 Now there was a man in Jerusalem whose name was Simeon; this man was righteous and devout, looking forward to the consolation of Israel, and the Holy Spirit rested on him. 26 It had been revealed to him by the Holy Spirit that he would not see death before he had seen the Lord’s Messiah. 27 Guided by the Spirit, Simeon came into the temple; and when the parents brought in the child Jesus, to do for him what was customary under the law, 28 Simeon took him in his arms and praised God, saying,

29 “Master, now you are dismissing your servant in peace, according to your word; 30 for my eyes have seen your salvation, 31 which you have prepared in the presence of all peoples, 32 a light for revelation to the Gentiles and for glory to your people Israel.” 33 And the child’s father and mother were amazed at what was being said about him.

34 Then Simeon blessed them and said to his mother Mary, “This child is destined for the falling and the rising of many in Israel, and to be a sign that will be opposed 35 so that the inner thoughts of many will be revealed–and a sword will pierce your own soul too.”

36 There was also a prophet, Anna the daughter of Phanuel, of the tribe of Asher. She was of a great age, having lived with her husband seven years after her marriage, 37 then as a widow to the age of eighty-four. She never left the temple but worshiped there with fasting and prayer night and day. 38 At that moment she came, and began to praise God and to speak about the child to all who were looking for the redemption of Jerusalem.

39 When they had finished everything required by the law of the Lord, they returned to Galilee, to their own town of Nazareth. 40 The child grew and became strong, filled with wisdom; and the favor of God was upon him.

________

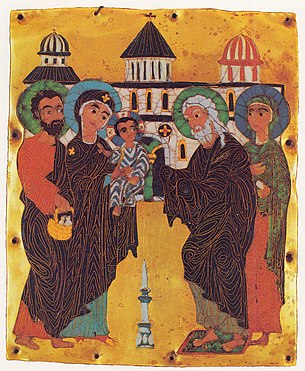

This past Sunday, 2 February, was the celebration of the Christian festival of Candlemas. It celebrates the presentation of the infant Jesus in the Temple, the story we just heard. Candlemas happens also to mark the halfway point between the winter solstice and the spring equinox. It marks, I suppose, our turning toward the turning toward the light. Hence, 2 February is Groundhog Day, too, when the matter of where in time we really stand is supposedly decided by whether a large rodent sees his shadow (more days of winter dark!) or not (welcome the approaching spring!). The day is a day of prediction, of prognostication, a day for claiming to fore-tell, to fore-know, the future, and thus to know just where we are, here and now, in the middle of things.

At least, in the case of the Presentation of the Lord, it is a day for claiming that once upon a time someone knew. When it comes to this story and stories like it in the Gospels, a cardinal rule of responsible interpretation is this: Ask not, How amazing is it that prophets, who naturally could not have known what was to come centuries after them, nevertheless supernaturally foretell and foreknow the events of Jesus’s life? Ask, rather, some fairly natural questions: Why is this writer drawing on the prophets as if they predicted Jesus? What is the writer trying to do?

(I say, this is a rule of responsible interpretation, and by that I mean it is a rule of faithful interpretation, too. For faith, I think, does not mean abandoning our natural questions for supposedly supernatural answers. No. Faith is courage to trust that our natural questions place us already in response to the presence of God.)

So, why is the writer drawing on the prophets as if they predict and prognosticate? Why does he depict two such characters—Simeon and Anna? What role do they play in the story? We might start to investigate these questions by noting that the literary theorists of Luke’s day recommended that a good story teller might start their narrative in medias res, “in the middle of things.” Start with some crucial action on which the drama turns, they advised, rather than at the chronologically earliest point. Starting in the middle of things creates immediate interest. The audience gets invested. The chronology of the story—how the characters arrived at that crisis, what happened to them after—all this can then be stitched together through flashbacks and foreshadowing. Tell a ripping yarn.

Now, Mark’s Gospel begins in medias res. It drops us into the crucial action of the baptism of Jesus. Curiously, Luke, who builds his story upon Mark’s, and whom scholars with better Greek than I consider the superior writer, does not commence his tale in the middle of things. Or at least, he affects not to do so. Luke opens with a dedication, promising his patron, Theophilus (a name that means, literally, “Lover of God”) an “orderly account.” Then the story starts, affecting to begin at the beginning, with predictions and prognostications of the birth of John the Baptizer and of Jesus. Following their fulfilment, we come to the scene where we, for our part, began—Mary and Joseph presenting their infant child in the Temple as Simeon and Anna interrupt the action.

Let’s ask again: What are Simeon and Anna doing there? Are they, and the other predictors and prognosticators featured in Luke’s Gospel, perhaps a piece of its promise of an orderly account? If he can describe an orderly account, the suggestion seems to be, then that is because a supernatural order was inscribed there, in events, all along. The prophets interrupt to explain it. What their predictions and prognostications, are meant to suggest, I suppose, is that everything is planned out. Nothing is unforeseen or unforetold in the divine plan.

If this seems believable to you, then let’s go on and ask another question: For whose benefit does the writer of Luke do this? Are we supposed to see this as good news to Mary and Joseph, perhaps? We might empathize and imagine that, even if the writer has his story all planned out, his characters would not experience it that way. Surely, they are in medias res when the angel Gabriel interrupts Mary, in the middle of an otherwise ordinary day, to announce the divine intent to impregnate her. So Simeon’s predictions, his prognostications, maybe they are meant to reassure us that Mary was reassured: everything is going according to a plan—if, in the middle of things, the beginning seems unclear and the end uncertain, know this child is “a light for revelation to the Gentiles and for glory to your people Israel.”

But maybe it’s not mainly for Mary’s benefit. If Mary is in medias res, how much more so Luke’s Theophilus? Imagine those late first century and early second century “lovers of God” for whom the Gospel is written. Imagine them living in the middle of perilous times, and caught between two precarious claims: on the one hand, that though he had died Christ had risen from the dead, and on the other, that Christ will come again. By the closing years of the first century, the former was a claim to which likely no one living could give firsthand testimony. It was a second- or third-hand claim at best. And the latter asserted a hope which, in the terms in which they had received it—that is, as an imminent return, “any moment now”—they must have found less and less supportable as the years wore on. So maybe this is why Luke interprets the prophets as predictors and prognosticators: in the middle of events his people are naturally unsure how to understand (since their beginning is receding ever further into shrouded memory, and their end is perhaps endlessly delayed) Luke’s “orderly account” interrupts uncertainty with seemingly supernatural reassurance that everything is going according to a plan. Even if the plan is no longer evidently as orderly as once was claimed.

If Luke and his contemporaries found themselves struggling to sustain an orderly account of the world’s salvation, how much more so us? Where do we stand in the middle of the things of God? With 14 billion years of cosmic past behind us, and maybe 5 billion more years in the future, I think it is safe to say: this is not a human-sized history. And so I think claims that the ways of God can be reduced to a story we can easily comprehend are claims we should treat with circumspection, if not suspicion. Like for instance Luke’s interpretation of the prophets—Simeon and Anna, and all the rest—as predictors and prognosticators.

We might not have thought about it, or we might have thought about it and decided to ignore it, but here is a fact: the predictors and prognosticators of the first century mistook their their sense of their place and time in history as the anchor-point for God’s ways with and in creation. Trustworthy guides they may still be in many respects, but not in that respect.

I’m not saying that I have a better grasp what the beginning, or the middle, or the end of God’s ways with us is. I only want to witness to the fact that we do not, and cannot, know for sure where or when—let alone how—we stand before God, here and now, in the middle of things.

Luke’s Gospel, indeed all of the New Testament, and the whole religious heritage of humanity contains a wealth of mythological stories: imaginary beginnings and ends, predictions and prognostications, fulfillments and foregone conclusions. These myths, some suppose, are meant to comfort us that a supernatural plan is making sense of it all, and that it will interrupt us soon, any moment now, to show us so. But the truth of the deepest myths is not in apparently describing a beginning of things nor an ending. Rather, the deeper truth of the myths is in how they crystallize our human condition: how it is to be thrown into existence, always and forever in medias res; and in how they call us to bear our condition responsibly, having to determine for ourselves, how best to begin and what best to aim to become, before God. So, if we insist on treating Biblical, mythological communication as literal description foreknown and foretold, then we may fail to recognize its most demanding call upon us, the call to being human before God.

Faith, then, is not believing that someone has a plan all figured out, even if we can’t figure it out. Faith is the courage to lead our lives as best we can, through the midst of things, trusting that we go before God. The way of the Lord, the prophets all say (and in this I affirm they are good guides), is not pre-prepared. It’s we who must prepare the way of the Lord. Somehow the way we live our lives prepares the way of the Lord. Indeed, the Biblical prophetic call to prepare the way of the Lord, when heeded, typically has the ironic effect of averting the need for the Lord to come. The prophets admonish us that the Lord comes, has always come, will always come, in and through our lives. It is in our lives that the divine life finds its way. When we prepare the way of the Lord, God doesn’t come to us. God doesn’t need to come to us. The way of the Lord is prepared in our walking. And thereby we may venture ever more deeply into the divine life. For those with eyes to see and ears to hear, the prophetic call turns our attention to this world as the way of the Lord.

So, then, can I say anything faithful about the road ahead? I will say, we don’t need prophets to issue supernatural predictions and prognostications. We can foresee what lies before us. We already know in rough form what is coming. Climate scientists of various kinds, for instance, inform us, with a high degree of probability, that we have bypassed all the ways we might have kept this God’s world from dramatic climate change. There will be—no, there already is—disruption, dislocation, devastation. What we do need prophets for is to call us to attend!—attend to our unbypassable responsibility to walk in the midst of this in such a way that we prepare the way of the Lord.

What does it mean to prepare the way of the Lord in this circumstance? How shall we walk the way of the Lord? You know, Maryville College has been known at times in its history as a “school of the prophets.” And the mission of the college still issues a prophetic call. We say that “Maryville College prepares students for lives of citizenship and leadership as we challenge each one to search for truth, grow in wisdom, work for justice and dedicate a life of creativity and service to the peoples of the world.” Because this statement is vague, there are many ways to participate in the MC mission. But, equally, there are many ways to deviate from it while telling ourselves we are doing good on some possible scale. But doing good on the largest possible scale is not identical to the aggregate sum of smaller scale goods, no matter how many, if they are not consistent with the mission. So the school of the prophets demands more. What does our mission mean today, in light of the road ahead?

Broken Journeys

An Address Given at the Samuel Taylor Wilson Chapel, Maryville College

11 September, 2018

Luke 10: 25-37 (NRSV)

25 Just then a lawyer stood up to test Jesus. “Teacher,” he said, “what must I do to inherit eternal life?” 26 He said to him, “What is written in the law? What do you read there?” 27 He answered, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbor as yourself.” 28 And he said to him, “You have given the right answer; do this, and you will live.”

29 But wanting to justify himself, he asked Jesus, “And who is my neighbor?” 30 Jesus replied, “A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and fell into the hands of robbers, who stripped him, beat him, and went away, leaving him half dead. 31 Now by chance a priest was going down that road; and when he saw him, he passed by on the other side. 32 So likewise a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side. 33 But a Samaritan while traveling came near him; and when he saw him, he was moved with pity. 34 He went to him and bandaged his wounds, having poured oil and wine on them. Then he put him on his own animal, brought him to an inn, and took care of him. 35 The next day he took out two denarii, gave them to the innkeeper, and said, ‘Take care of him; and when I come back, I will repay you whatever more you spend.’ 36 Which of these three, do you think, was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of the robbers?” 37 He said, “The one who showed him mercy.” Jesus said to him, “Go and do likewise.”

___________________

Cognitive scientists who study metaphor have theorized that a great many metaphors are based on our experience as embodied creatures making our way in a physical environment. So, for instance, it is “natural” to us to speak metaphorically of our live as journeys, with points of departure, destinations, and, one hopes, interesting and enriching experiences along the way. Such metaphors permeate Jewish and Christian scripture. The Book of Exodus is a story of the physical journey of the children of Israel from slavery in Egypt to freedom under the reign of God in the land promised their ancestors. That story is already greatly embellished, but the image of a journey, from slavery to freedom, becomes a metaphor that resonates through the entirety of Scripture, and in the personal experience and shared histories of the people who read it as Scripture.

A weakness of metaphors, however, is the way they break on those bonds of our existence, which no amount of embellishment can ease. We may tell ourselves the stories, but sometime, one way or another, life is going to stop you in your tracks and shake you down. Some of us never get to start again. In life, not everyone gets to reach their long hoped-for destination. But for all of us, the end of the road is unreachable.

Our journeys end, never not abruptly. The way goes on, but we do not.

No wonder, then, that we wonder, “What must I do to inherit eternal life?”

* * *

Seventeen years ago on this day (it happened to be a Tuesday that year, too), Chrissy my wife and I were living with her parents in New Orleans and we were starting the last preparations for our new jobs directing a study abroad program in Comparative Religion and Culture. In a week’s time – September 18, 2001 – we were to travel to San Francisco, where we would meet the 25 undergraduate students from across the United States, with whom we would travel the full academic year through Taiwan, Thailand, India, Nepal, and Turkey.

Seventeen years ago on this day, I say, we ate breakfast, while the morning news played on TV. Was I shaving? – I think so – when the news began to break. A terrible accident in New York City. Our program was headquartered in New York. An airplane crashing into the World Trade Center. I am watching, eighteen minutes later, when the second plane breaks the face of the South Tower. Who can believe it? Peter Jennings, the then-anchor of ABC news, wants not to believe it. He is inside a studio, uptown. The North Tower falls in upon itself in plumes of smoke and pulverized concrete, and Jennings’ reporter at the scene, Don Dahler, tells him, “The second building . . . has just completely collapsed.”

And I remember Jennings interrupts – I think he’d heard well enough but thinks he must be hearing things – Jennings interrupts to say, “I’m sorry, what was that?” But Dahler’s voice weirdly insists, both plaintive and implacable, “The entire building has just collapsed . . . . it’s not there any more.”

Our journeys end, never not abruptly. The way goes on, but we do not.

No wonder, then, that we wonder –

* * *

“What must I do to inherit eternal life?” an expert in the law asks Jesus. In a classic teaching move, Jesus questions the question: “What is written in the law? What do you read there?” It’s a question crafted to call out of the student something revealing. For the second of the commandments, which they both have in mind, contains a crucial ambiguity. Its source is Leviticus 19:18. The Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures renders that verse to command love of neighbor. But the Hebrew it translates is indecisive. Hebrew was written in consonants only. Readers supplied vowels based on the context. Often, then, readers had to specify for themselves in speech the sense of a word which, as written, could mean several things. That is the case here. So Jesus’s question, “What do you read there?” asks, “How will you decide to read this word.”

The word at issue is this: ער. Depending on how a reader decides, the word could be this: רֵעֲ, “neighbor,” or – and now it gets interesting – it could be this: רָע, “wicked one,” “enemy.” So that question, “What do you read there?” – oh, it’s a tough question. Jesus demands your candour, demands that you disclose a deeper, even if a discomforting, understanding of the choices you make about whom, and how, you will love.

“You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbor as yourself.” The lawyer chooses the “easier” reading. Still, Jesus congratulates him: “You have given the right answer.” (Indeed, the other synoptic gospels identify these commandments as the basis for understanding anything of Jewish law and prophecy.) But then Jesus adds, ironically, “Do this and you will live.” It is not enough to give the answer; you have to live the answer. Note, Jesus doesn’t say anything about the lawyer’s wish to inherit eternal life. It’s as if he says, “What are you wondering about eternal life for? Are you even alive now? Do this and you will live!”

Now who needs telling that those two commandments are easier said than done? The lawyer knows it. Perhaps, hoping to make his reading of the commandment easier still, he asks his infamous question, “And who is my neighbor?”

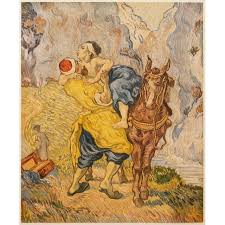

So Jesus tells a story of a man going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, who fell into the hands of robbers, who stripped him, beat him, and went away, leaving him half dead; a story of a Samaritan who becomes a neighbor to this stranger, this enemy in distress, and, showing him mercy, loves him as himself. “Go and do likewise.”

I would like to do likewise. I would like to live. But I also want to interrupt. I want to break through the perfect face of Luke’s fourth wall, and call out, as if from the gathered crowd, “Stop telling us this story! ‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind?’ Do you know how hard it is to love God? When the life we are given us stops us in our tracks, shakes us down, and leaves us half-dead at the roadside, how are we to love God? When ones we love dearest are gone, nowhere near their hoped-for destinations, how can we call God our neighbor? Is God, who gives us these broken journeys, not sometimes more like an enemy? ‘Love your enemy as yourself? Do this and you will live?’ Have mercy!

It seems to me that a danger for us who would be seriously religious in the United States today is that the popular culture celebrates willingness to love God with our heart, but not our mind, so we are passionate but ignorant; and to love with our strength, but without soul, so we are forceful but unfeeling. Wilfully ignoring the shadow side of God, refusing to feel the theological depths of our brokenness – these failings make it all but impossible for us to read the second commandment aright, let alone do it – that we shall love our neighbors as ourselves and be neighbors even to our enemies.

* * *

We spoke with our dean in New York. He was safe, but clearly, our TVs told us, many were not. Their journeys were ended. And was ours broken, too, before we even got started? We didn’t know, but as the day wore on into night and another day, we resolved to try to go on. Whatever the attacks meant for the future, we concluded that now, more than ever, the mission of the program mattered: to be out there in the world, learning to see, and be, neighbors, not enemies. A week later, 24 of the original 25 students met us in the San Francisco airport – one had caught a Greyhound from Maine to California! – and we flew off into the world.

* * *

Luke sets the story of broken journeys from Jerusalem within a narrative of Jesus’ journey there. There, he has already said, “The Son of Man must undergo great suffering, . . . and be killed, and on the third day be raised.” And he does not deviate. Moreover, he teaches, “If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross daily and follow me. For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will save it.” (Lk. 9: 22-24) They follow this ever stranger person, a person for whom broken life is the price worth paying to love God with all his heart and mind and soul and strength, to become a neighbor to enemies and love neighbors as himself.

Not that they read him right. Knowing his life’s journey is about to end in extreme abruption, they are afraid. They would rather inherit eternal life. Him they abandon, half dead, dying. Only later, they will learn to see the secret, that the person on the broken journey is their God and neighbor.

Do we read him any more right now? Don’t we keep wishing for unbroken journeys, even if it means abandoning our enemies, our neighbors, our God?

* * *

I know it is controversial to say so, but I think Love Actually might be the greatest of films about 9/11. It is a film lost in fantasy in many ways, as we are. But how beautiful it is in defiantly celebrating love, even unpretty loves, under the awful pall of the terrorists’ attack on the life we knew and our escalation of violence across the globe in reaction. As the film begins, David, the British Prime Minister fancifully played by Hugh Grant, speaks:

“Whenever I get gloomy with the state of the world, I think about the arrivals gate at Heathrow Airport. General opinion’s starting to make out that we live in a world of hatred and greed, but I don’t see that. It seems to me that love is everywhere. Often it’s not particularly dignified or newsworthy, but it’s always there – fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, husbands and wives, boyfriends, girlfriends, old friends. When the planes hit the Twin Towers, as far as I know, none of the phone calls from the people on board were messages of hate or revenge – they were all messages of love. If you look for it, I’ve got a sneaky feeling you’ll find that love actually is all around.”

Yes, indeed. All God’s creatures that can, loving however they can, in fragmentary, but always glorious, confusion. Yet, we are called, from deep within the glory, to love wholly. To gather up as neighbors all our brokenness: hearts and minds and soul and strength, to live in the life of God. Do this and we will live. What is it, to live eternally? Now, more than ever.

Amen.

Was Jesus Happy?

An Address Given at the Samuel Taylor Wilson Chapel, Maryville College

10 October, 2016

Luke 6:20-30 (GNT):

20 Jesus looked at his disciples and said,

“Happy are you poor;

the Kingdom of God is yours!

21 “Happy are you who are hungry now;

you will be filled!

“Happy are you who weep now;

you will laugh!

22 “Happy are you when people hate you, reject you, insult you, and say that you are evil, all because of the Son of Man! 23 Be glad when that happens and dance for joy, because a great reward is kept for you in heaven. For their ancestors did the very same things to the prophets.

24 “But how terrible for you who are rich now;

you have had your easy life!

25 “How terrible for you who are full now;

you will go hungry!

“How terrible for you who laugh now;

you will mourn and weep!

26 “How terrible when all people speak well of you; their ancestors said the very same things about the false prophets.

27 “But I tell you who hear me: Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, 28 bless those who curse you, and pray for those who mistreat you. 29 If anyone hits you on one cheek, let him hit the other one too; if someone takes your coat, let him have your shirt as well. 30 Give to everyone who asks you for something, and when someone takes what is yours, do not ask for it back.

________________________________

In one of his great Essais, the 16th century Frenchman, Michel de Montaigne, wrote that we should not be deemed happy till after our death. For, he explains, mortals such as us, “no matter how Fortune may smile on them, can never be called happy until you have seen them pass through the last day of their life, on account of the uncertainty and mutability of human affairs which lightly shift from state to state, each one different from the other.”[1]

In saying so, Montaigne was following in a tradition of wisdom that stretched back to the ancient Greeks and Romans. Indeed, to refine his point, he calls on the wisdom of Solon, the Athenian law-giver. In seeking happiness, Solon, he says, was indifferent to fortune and misfortune. For him, happiness depended on “tranquility and contentment of … spirit,” and “the resolution and assurance of an ordered soul.” (86) Happiness, in the long view cultivated by Greek and Greco-Roman philosophers, including Solon, meant to fulfill the distinctive potential of one’s nature through all the course of life, and to bring it to a culmination in the dying of a “good death,” free of fear.

There is something a bit funny, isn’t there, about refusing to declare that someone is happy until they are dead? It gives new meaning to the proverb, “Better late than never,” doesn’t it? But the wisdom is clear, I think: no matter how secure one’s circumstances might seem to be, and no matter how well one might seem to be leading one’s life, the risk of failing to actualize one’s potential, whether by accident or through one’s own fault, can never be ruled out of the range of possibilities. Don’t ever presume! I mean, consider the unhappy fate of Brangelina.

But my question is, Was Jesus happy? It must have been a question on the minds of the writers of the New Testament Gospels, for each of them portrays Jesus as providing the very model of a good death. He is resolute to the end. Yet, it is also likely that, if their stories were to inspire their audiences to cleave to the Christian way, then the writers needed to portray Jesus as dying a death so good, one might wonder if he was not superhuman. For by any objective standard of the time, Jesus did not die a happy person. A sudden and secretive arrest, followed by the savagery and the public shame of crucifixion, figured in no first century handbook to happiness. And then there are those dreadful words in the Gospel of Matthew: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” No, we should acknowledge how horrifying his dying must have been; how the promise of humanity in him was desecrated. How unhappy that man of sorrows.

But what if Jesus had been engaged in the pursuit of happiness? How—what way—was he running that race, before he was taken out of competition? One of the few clues we have is the Gospel we heard a short while ago. There are problems here, of course: these so-called “Beatitudes” appear in both Matthew and Luke, but differently, and we have no unassailable reasons to believe that the character of Jesus that emerges in either story is a close reflection of Jesus of Nazareth. Still, however Jesus actually said these things, or if he said them at all, or if, instead, they enunciate a lesson followers drew for themselves from having shared in his way, it is utterly striking that Jesus proclaims a person’s happiness does not depend upon the fulfillment of a natural potential—not the obvious potential, anyway.

The word for “happy” in these statements, makarios, is pointedly not the word the philosophers used to guide disciples to their goal. Makarios can also be translated as “fortunate,” or “lucky,” or “blessed.” In fact, oi makarioi—“the blessed ones”—was a term employed in referring to the Gods, who, presumably, enjoyed perfect tranquility and contentment of spirit, neither having to strive for it nor struggle to preserve it, as we mortals must. However, the term was also used in a more slangy way to speak of the upper classes of the Roman Empire, the elites in a desperately unequal society. These were the ones on whom fortune smiled; whose existence must have seemed charmed to the vast, immiserated majority. Today we might call them, with a similarly ironic edge, the “beautiful people.”[2]

Jesus’s words, then, are a poke in the eye to them. How utterly striking, when Jesus looks upon the defenceless, the exploited, the excluded, and sees what he then says: You, you poor, you are the beautiful people. And you, the ones who are hungry and have nothing to eat, you are the beautiful people. You who are grief-stricken, hopeless, who can’t keep from crying, you are the beautiful people. If you are hated, rejected, mocked and slandered, then be happy, for you are the beautiful people. You, in short, are God’s favorites.

Can we say such things? Do we truly see them? Oh, that we had a divine eye. Oh, that we might have eyes to see and ears to hear.

But hear this, too: If the writers of the gospels are to be believed, the poor, the hungry, the hopeless can be happy because a great reward is kept for them “in heaven.” I don’t believe them. If you have heard me preach here before, lo! these 10 years, then you’ve heard me return, again and again, to this tension between the words of Jesus and the worldview within which they made sense to him and his followers, a worldview which make little sense to us—well, at least to me. It makes me unhappy when Christians reassure themselves or, worse, others, that poverty, hunger, hopelessness in life are not so bad, because Jesus is coming to take people away to a place called Heaven, if he hasn’t already gotten them there. It makes me even more unhappy when Christians go on and convince themselves that it matters more that we believe there is a place called Heaven, and a God in it, then that we see this world and those in it as Jesus seems to have done, with a divine eye.

If being faithful means believing all the same things the New Testament writers, maybe even Jesus himself, believed about life, the universe, and everything—well, what a waste of our potential. We have a different physics, a different biology, a different cosmology, a different economy; it seems to me there is nothing to be gained from turning our back on these truths. So many Christians routinely ignore Jesus’s insight into happiness, his dedication of his life to the service of God’s favorites. I think my disagreement with the gospel writers on the likelihood of a supernatural heaven might be excused.

God, the kingdom of God, is not “compensation.” And this is the nub of my disagreement. Jesus does not say, Sorry, folks, there’s nothing to be done about your present unhappiness, but don’t despair—you will be happy later, in Heaven, it’s only fair! No, he says, to the poor, the exploited, the excluded: You are the beautiful, the blessed ones; you are God’s favorites. And he gives his life to them.

St. Paul saw the kingdom of heaven right there in the gift of that human life. “God was in Christ,” he wrote to the Corinthians, hoping to interrupt their squabbles over who really were the beautiful people. “God was in Christ, reconciling the world to himself.” Jesus’s inversion of conventional wisdom as to who is happy, and who is not, is not meant as a promise of eventual compensation. It is meant to motivate us to reconciliation. For all my doubts about Jesus and his followers, my faith in Christ is he lived in God, as God lived in him, and concretely in the life he lived in companionship with the hungry, the helpless, the hated.

If that life is happy, the metric can hardly be the classical canon of self-fulfillment, can it? No, with his divine eye Jesus saw unsuspected potential in us, an immeasurable potential for reconciling self-transcendence toward one another. Jesus’s own death was not terminal, but germinal. His life did not end with him. It transcended itself, inspiring his followers, down through centuries, to follow him where he might be found, among the poor, the exploited, the excluded. Deem no one happy until their death. That is good wisdom. But don’t be fooled into thinking we know exactly when death has come. The spirit of Christ inspires the disciples of Jesus to live in God, with a potential for happiness ever greater and ever new. I don’t mean trying to make someone happy up in “Heaven.” I mean, we bring the spirit of Christ nearer its true and endless fulfillment, when God will be all in all, when we lay down our life in Jesus’s way. This is the gospel as best I understand it today.

[1] Michel de Montaigne, The Complete Essays, trans. M.A. Screech (New York: Penguin Books, 1991), 85.

[2] In Australia, we’d call them lucky bastards.

Liberating God

A Sermon Delivered at Maryville College Center for Campus Ministry, Maryville, Tennessee

October 13, 2015

Readings: Job 38:1-7, 34-41; Mark 10:35-45

Then the LORD answered Job out of the storm: “Who is this that darkens counsel by words without knowledge? Gird up your loins like a man. I will question you, and you shall declare to me. “Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth? Tell me, if you have understanding? Who determined its measurements—surely you know! Or who stretched the line upon it? On what were its bases sunk, or who laid its cornerstone when the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God shouted for joy? Can you lift up your voice to the clouds, so that a flood of waters may cover you? Can you send forth lightnings, so that they may go and say to you, ‘Here we are’? Who has put wisdom in the inward parts, or given understanding to the mind? Who has the wisdom to number the clouds? Or who can tilt the waterskins of the heavens, when the dust runs into a mass and the clods cling together? Can you hunt the prey for the lion, or satisfy the appetite of the young lions, when they crouch in their dens, or lie in wait in their covert? Who provides for the raven its prey, when its young ones cry to God, and wander about for lack of food?”

The great vocation of modern life has been the call to autonomy. Any of you who has even passing acquaintance with HUM201 know the famous line from Immanuel Kant’s essay on enlightenment: “Sapere aude!” “Dare to think for yourself!” In Kant’s imagining, this courageous act of exercising one’s reason is simultaneously to throw off heteronomy, to throw off one’s need to be instructed by others how to think. It is the one necessary condition of being free.

Autonomy. It is a praiseworthy and a perilous vocation. Kant had a hard-won confidence in the guiding, self-governing light of reason. Yet his confidence seems not after all to have been purely rational. It rested also in the incorruptibility of his personal character and in his hopeful estimation of the times in which he lived. By contrast, the great majority of us, lacking Kant’s particular excellences and placed in different social and economic circumstances, slouch around the life of autonomy rather more slovenly than Kant hoped for us. Sensing the difficulty of following our reason’s lead, we have largely replaced rational self-control by the law of consumerism: “I want what I want, and what I want I should get.” (I suspect this is especially, even if not only, the case for us men.) So, without regard to whether what we want is worthy of desire, we ricochet through life: vectors of demand, atoms of appetite, increasingly incapable of real freedom, true fellowship.

When our sense of ourselves is so ill-defined, so in-finite, it’s small wonder that our consumerist freedom produces vertigo. This I think explains the title sequence of the television series, Mad Men, in which a figure – the show’s main character, Don Draper, presumably – is falling past skyscrapers, past advertising images, but never accelerating, never making impact, just falling, falling through boundless space. The show is in no small part about the hypertrophic spread of the law of consumerism. If we surrender all the senses by which we appreciate the life of the world that moves through and around us, if we value only the sense of having, then we become entirely disoriented to the living world of values, a world whose life cannot be had but must be revered. If we value only the sense of having, then instead of finding our place, we fall prey to one or another heteronomous power. Having to have them, really they have us. “They” are the concrete gods that govern our lives: those clothes you have to have; that grade you have to have; the conveniences you have to have; the admiration of others you have to have; the revenge you have to have; the justice you have to have, whatever it might be that you have to have.

Paradoxically, such selfish having to have tends toward the loss of a self worth having. The in-finitude of our desire can overwhelm and even destroy us. Don’t despair yet, though! For the self that has to have has a last, ingenious manoeuvre: you can have God want what you want, God infinitely desiring, and therefore justifying, your in-finite insistence on getting what you want.

But what deep bondage this brings, when we cannot exempt even the infinite from our in-finite demands, our wayward hunger to have.

* * *

Job discovered himself in this sorry position. Job was a very good man, who suffered very bad afflictions. He had it all, and then all of it was taken away: his wealth, his children, his bodily well-being. On the story’s account, God permits the taking of it all away. Job’s well-being is God’s wager in a bet with Satan – just to make it interesting, I suppose. In the ruins of his life, conscious of no fault in himself that would give reason for this terrible reduction, Job gathers up the fragments of his desire. He hungers for just one thing. Job has to have justice, and God, he argues, owes it to him.

The reading we heard is an excerpt from God’s reply to Job’s demand. I call it a reply, but it is a rebuke, really, in which God makes patently clear that Job has no idea who he is talking to. Job may think he knows what this justice is, that he has to have. And Job can insist that God has to give him what he thinks he has to have. But Job, God taunts, has no handle on the order of creation. God creates everything, is present in everything: in all order, in all chaos. God revels in it all, exults in the sheer power to create everything, anything – and to bring it to an end. God glories in absolute freedom from having to have. The speech might be distilled to this: “Let go of your having to have; regain your senses of the splendor of creation.” God’s speech to Job can shatter selfish delusion, and set us free to glory in God, to take our place in the glory of God.

* * *

Who do you think you are? Do you really think God cares about what you think you have to have? Do you really think God cares about finding you, say, a convenient parking space? Do you really think God cares about you being fashion forward? Do you really think God has to have you get that grade? Do you really suppose that your concerns are at the center of God’s?

Whether in times of deeper joy or times of harrowing sorrow, there are plenty of others like us. Do we really suppose we are God’s chief concern?

Consider the meaning of our lives. Will we find/do we have/what if we lose satisfying work at which we can succeed? Will we find/do we have/what if we lose loved ones and ones who love us? Yet there are plenty of others, rich in years and all those accomplishments, and others cut off short all too soon. Do we really suppose, then, that ours are God’s chief concerns?

Our people, our country, our faith, this proud species of ours – do we really suppose these are the center of God’s concerns? Come to your senses! Has God not created this whole planet, teeming with life of all kinds, sometimes cooperating but always competing to survive? The beauty and the carnage of life and death on earth defy comprehension. If God is such as to have something in mind here, whatever that is, don’t you suspect we might not be at its center?

Anyway, one day life on this planet will be extinct. Why then this planet, why our star, why all the stars? For what this whole creation that exceeds in its infinity the hold of our in-finite desire? Whatever for? Whatever for, if even, in some unimaginably distant future, this entire universe collapses in upon itself or dies in infinite dissipation? Whatever for? What the heck do we know about the Creator’s concerns? Let us come to our senses!

* * *

“Who is this that darkens counsel by words without knowledge?” (Job 38:2)

“Then Job answered the LORD: ‘I know that you can do all things, and that no purpose of yours can be thwarted. Who is this that hides counsel without knowledge? Therefore I have uttered what I did not understand, things too wonderful for me, which I did not know.” (42:1-3)

This creation, too wonderful for me: glory of God who creates it, just so.

Infinite time, infinite space, galaxies upon galaxies, stars upon stars. Too wonderful to grasp: glory of God who creates it just so.

The ferocious fusion of our star. The eons-long accretion of dust and debris, rubble coagulating into asteroids, even planets. Too wonderful to grasp: glory of God who creates it just so.

This planet, queerly, happily compacted, just so, sun and moon, time and tides, and life becomes possible. Too wonderful to grasp: glory of God.

Life become actual! Let us come to our senses! Sense divine glory in the stirrings of diverse habitats and delicate organisms, living and dying all. Sense glory of God in the baffling emergence of our humankind. Human peoples, their histories, their nations, their faiths, their lives. Too wonderful to grasp: glory of God.

Your life. You. In life or in death, glorious in God!

Raise your fingers; touch your throat; find your pulse; do you feel it? Closer to you than you are to yourself, glory of God more real than any in-finite having to have.

Now look around you. Look to your neighbor. Reach out, and try find their pulse. The glory of God. Then be liberated from selfish delusion, be freed to be your part in God’s glory. For even the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many. (Mark 10: 45)

Stranger

(Part of the 2014 Chapel Series, “Who Do You Say That I Am?”)

November 18, 2014

Maryville College

Text: Matthew 25:31-46

Dare we understand you, Man of God?

Dare we walk in your way?

Surely you know our griefs too well.

You know our pain.

Dare we share in your suffering, Man of God?

He will be raised and lifted up.

He was despised.

He was spurned by us.

Surely he took up our frailties.

Yes, he carried our sorrows.

Dare we understand you, Man of God?

Dare we look upon you?

Surely we see our ugliness,

Our sin in you.

Dare we look to you, O Man of God?

He was raised and has ascended.

God shows us love,

Shows us love by this:

While we were still enemies,

Yes, Christ has died for us!

Dare we understand you, Man of God?

Dare we die with you?

Surely you know death’s bitterness,

Its scars on you.

Dare we take our cross and follow you?

It’s about 25 years since I wrote that song, in which I sought to reckon with the strangeness of that Man of God, Jesus. After 25 years, the me who wrote that song seems a little strange, too. I was a student at Sydney University, getting ready to graduate with a B.A. I had been a leading member of the equivalent of InterVarsity Fellowship. The song expressed my unease with the “cheap grace” of an evangelical middle-classism that sometimes seemed to give lip-service to Jesus as Lord while evading the costs of becoming like him. Better to be nice – and keep distance from those who could not be – than to know our griefs, our pain, let alone those of the crucified.

But the me who wrote the song was a little naïve, a little innocent of history. The apocalyptic preacher from Nazareth who insistently – but mistakenly – believed that a divine kingdom of righteousness would, in his lifetime, drive out and destroy all evil from the world is even stranger than I thought then. His world and my world are, in many ways, worlds apart. He lived in a world in which he saw the armies of heaven at night maneuvering about the sky. I think they are stars. He lived in a world in which he fought demons who took possession of vulnerable people to do them harm. I suspect he had a marvelous and enviable talent for helping people with psycho- and sociosomatic illnesses.

And how strange must we look to Jesus, if he were to come among us! He, who supposed history was ending with his generation! What would he make of our landing a space probe on a comet traveling at thousands of kilometers per hour, millions of kilometers from earth? What would he make of our technical prowess in the diagnosis and treatment of neurological and other disorders? Could he begin to understand who we are?

“Who do you say that I am?” Stranger.

One of the reasons we dwell on that question, “Who do you say that I am?”, is that we have no real idea who Jesus said he was – if it matters.

A little over a century ago, in his definitive Quest of the Historical Jesus, Albert Schweitzer concluded, “Jesus as a concrete historical personality remains a stranger to our time . . . .” This conclusion has lost none of its bite. Schweitzer said more, though. I have cut him off in mid-sentence. He wrote: “Jesus as a concrete historical personality remains a stranger to our time but His spirit, which lies hidden in His words, is known in simplicity, and its influence is direct.” (Schweitzer 399) And the closing paragraph of this essential study is justly famed:

He comes to us as one unknown, without a name, as of old, by the lakeside, He came to those men who knew Him not. He speaks to us the same word: “Follow thou me!” and sets us to the tasks which He has to fulfil for our time. He commands. And to those who obey Him, whether they be wise or simple, He will reveal Himself in the toils, the conflicts, the sufferings which they shall pass through in His fellowship, and, as an ineffable mystery, they shall learn in their own experience Who He is. (Schweitzer 401)

Schweitzer’s lesson is clear. Jesus never called anyone to form a fan club. He called disciples to live as he lived. It seems that Jesus was pretty uncompromising about this. If Matthew’s gospel is any reliable guide, Jesus could be forgiving, but he commanded nothing less than perfection in accordance with the Jewish Torah. He recognized no alternatives.

A stranger Jesus is to me here, too. For I live in another world where, in spite of vicious fundamentalisms and ferocious religious violence, many of us suspect there is not just one true religion. I’ve learned treasured lessons from neighbors of other faiths (and none) that I could not teach myself. So I feel at least a little quizzical about the many and various gods, not excepting my own.

But I won’t go on in this way now because, for all his strangeness, I happen by accident of birth and upbringing (and doubtless a dozen other reasons of which I am unaware) to be one of those people for whom this stranger seems at the same time to be the source of a power to overcome estrangement. He is – but of course in secret – God and my neighbor:

‘Lord, when was it that we saw you hungry and gave you food, or thirsty and gave you something to drink? And when was it that we saw you a stranger and welcomed you, or naked and gave you clothing? And when was it that we saw you sick or in prison and visited you?’ And the king will answer them, ‘Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.’ (Matt. 25:37-40)

So while I do not wish to belong to a fan club for Jesus, I do hope to become a good enough disciple to live as he lived, so that I might know and love my neighbors as myself, and we might be strangers no more.

I fairly suck at it for now—partly because I think I do understand something of where Jesus leads, and I have not overcome my middle-classism enough to not be afraid. But there are some who go before us.

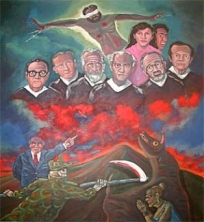

For instance, also 25 years ago, just this past Sunday in fact, six Jesuit priests who lived and taught at the Central American University in El Salvador, along with their housekeeper and her daughter, were murdered in the middle of the night, by U.S.-trained Salvadoran military forces. Their offense was to aid poor Salvadorans to defend their human rights in a situation of abusive inequality and savage civil war. Those men: Ignacio Ellacuría, Ignacio Martín-Baró, Segundo Montes, Juan Ramón Moreno, Joaquín López y López, and Amando López; and the women, Elba and Celina Ramos; understood that to live as Jesus lived means to take the crucified people down from the cross. But sometimes, the Romans come for you, then, too.

Are we then disciples? Or are we content to pretend being Romans?

The Jesuit Martyrs. Mural from the Chapel of the University of Central America, San Salvador

Dare we understand you, Man of God?

Dare we die with you?

Surely you know death’s bitterness,

Its scars on you.

Dare we take our cross and follow you?

Amen.

Will and Jamie’s Adventure Down Under

What Is the Work of Faith?

What Is The Work of Faith?

September 10, 2013

Maryville College

Matthew 6: 20-33

I welcomed Anne’s words last Tuesday on what she thinks the title of this year’s chapel series means, as well as on her own reservations about what we could take it to mean. “Faith works” is obviously an ambiguous phrase. Is it a simple, two word declarative sentence asserting that “faith works” – that is, that faith is a useful tool or a skillful technique for getting us what we want and where we want to be? Is it a classificatory term, distinguishing one kind of work or activity among others? “Faith works” as opposed to, say, “secular works”? Is it an exclamation – “FaithWorks!” – like maybe the title of the next big show from Cirque de Son (That’s the name I came up with for an imaginary and ghastly “Christian” Cirque de Soleil? Get it? Soleil. Sun. But, “Son” spelled s-o-n, not s-u-n.) Or (my last alternative), is “Faith Works” meant to alert us to something about faith’s own nature? Perhaps that faith is its own dynamic power, that faith of itself works change and transformation of some kind? Then faith matters for its own sake, and not just in reference to further ends, to specious limitations of the sphere of religious concern, or to dismal trends in popular taste.

Of these possibilities, I am particularly interested in the first and last. The first, as Anne so adroitly warned us, instrumentalizes faith. It puts faith to work as a tool in service to other, presumably more valuable ends. I’m tempted to condemn this unequivocally, as a bad and blameworthy thing to do, but I suspect that would not be entirely fair. For it seems as though faith may invite its own instrumentalization. Interesting studies in the last decade or so have found correlations between religious practice and, for example, health and healing, sexual satisfaction, a general sense of contentment. These studies beg many questions, about how the terms of inquiry are defined, about research design, and so on, but more than a few of them are careful about their terms and serious about design. So, then, if I want better health, better sex, a better life all around (yes, please), and if faith works to give me those things, well, Praise the Lord!

But this attitude seems problematic – to my way of thinking, at least – because the work of faith, as I conceive it, concerns bringing us before God, and God before anything else. But if we instrumentalize faith then we value God for the sake of something else, in which case that “something else” is really our God. Of course we do this all the time. We “believe in” God, without really giving much critical thought to what God is really like. We “have faith” that our God will give us what we want and get us where we want to be. But any God whose chief worth is to serve my wants is what in Australia we would call a Claytons God: the God you have when you’re not having God – the God for those who don’t care to be God-intoxicated, the God you have when you want to stay in control. In other words, no God at all.

Unlike a Claytons faith in a Claytons God, faith, at least as I conceive it, will not settle for less than an object of truly ultimate concern, that absolutely transcends every God I can put at my disposal, every idol of my self-interest. And if faith cannot be satisfied, still it does not rest.

Now, I admit, I’m a person of a particular time and place and experience, and my idea of faith likely shares in my personal limitations. Perhaps faith has not always been this restless inner drive toward something we can never have. Or perhaps faith is just one way of relating to God, a way that was unimportant, that became very important, and that probably will lose its importance someday. Worse, maybe I am just foisting my personal mid-life psychodrama upon you, under the tragic delusion that I have some sane and healthy idea what faith is! Maybe I should just relax, not worry so much about what God is really like, and enjoy the fringe benefits of faith.

Well, maybe if I was someone else, I could. But I am not someone else, and faith as it works in my life is mostly like a restless, driving force that will not settle for a Clayton’s God; Faith wants a full-strength God, however much I may be in two minds about that. This is the real irony about my talk today: not that I am mistaken about faith’s work, but that I don’t truly believe myself. I’m in two minds, crying “Lord I believe, Help my unbelief!” Am I, in my whole person, a person of faith as I am describing it? Surely not. Faith has much work to do with me, before my testimony can be true.

So perfect faith lies ahead of me and likely always will. Perhaps true faith can nevertheless be something less than perfect. The great Protestant theologian, Paul Tillich, treats faith as an intrinsic mark of existence as such; faith for Tillich is a kind of basic dimension of being human. In other words, faith itself I not something you do (or don’t do), have (or don’t have). In everything a person does, his or her faith is manifested. Faith can be considered then not only in terms of its divine object, absolutely transcendent and ever elusive, but also in terms of its own dynamics. Faith is a way you are. You may be in a bad way. Maybe you’re in a good way. Or, like me, perhaps the symptoms are confusing. But because faith works in us to clear our way of Claytons Gods, to set aside the idols of self-interest, faith shows itself as a focusing power that would concentrate our scattered souls, for better or worse, before the presence of what ultimately matters.

Can anybody live well with such faith?

I was very lucky to spend some extended time this past summer in China and in Argentina. In China, I was engaged in a Confucian studies program, reading classic Chinese philosophical and religious texts with Western and Chinese academics. In Argentina, I was meeting with people who, in a variety of ways, serve God by joining with the poor and marginalized to transform the values and priorities of their society. In these two places, I was reminded of two important, and I think overlapping, ways in which faith can take effect and issue in a life lived well in the presence of what ultimately matters.

One of the most striking qualities shared by the people I met in Argentina was unassuming courage. From 1976-1983, Argentina suffered what has come to be called the Dirty War, a largely indiscriminate campaign of disappearance, torture, and murder carried on by a military dictatorship in the name of combating a violent communist insurgency. I met Maria Eugenia, whose sister was arrested and held without charge for seven years in a prison where torture was routine. Maria was a teenager at the time. She saved her sister from some of the worst by coming to visit her sister every week. Maria was subjected to all manner of harassment, including being strip searched and handled. It routinely took three hours to pass through these “security procedures,” after which she had half an hour to see her sister, with a pane of glass to separate them. Many women received no visitors, because of course any visitor became a suspect.

I met Aida Bogo, one of the founding members of the Madres de Plaza de Mayo, mothers whose children began disappearing in the Seventies. No one would help them find their children – not the police, certainly not the military. So the Mothers began to assemble in front of the presidential palace each week, silently calling for the truth. They were harassed by police officers and soldiers. They were infiltrated and betrayed by members of the military. Some of the Mothers themselves disappeared and were never seen alive again. Aida is 84 and awesome. She lost her 22 year old daughter in the Dirty War. “What do you do when you’re afraid?” one of us asked. “I’m always afraid,” she said, “but I just keep going.”

Faith shows itself in courage, courage to never settle for less than truth in love. The courage of faith is not the opposite of fear. The courage of faith is not bluster and intimidation of others. It is utterly honest about fears and frailties, and embraces them in the concentrated presence of what ultimately matters.

The Confucian virtue of cheng is commonly translated as “sincerity,” although it is not so far-fetched to translate cheng as “faith,” and it certainly is not at all off track to see cheng, like courage, as work of faith. The person who is cheng, sincere, entrust herself without any pretense. The person who is cheng seeks simply to present herself in the presence of what ultimately matters, unconcerned to benefit for herself but simply to be herself. So highly does the Confucian tradition value cheng that the sincere person is sometimes envisoned as entering into concentrated communion with the ultimate creativity that courses through all reality, the dao. The classic text, Zhongyong, has this to say:

Only those who are absolutely sincere can fully develop their own nature. If they can fully develop their own nature, they can fully develop the nature of others. If they can fully develop the nature of others, they can then fully develop the nature of things. If they can fully develop the nature of things, they can then assist in the transforming and nourishing process of heaven and earth. If they can assist in the transforming and nourishing process of heaven and earth, they can thus form a trinity with heaven and earth.” (Zhongyong 23, Tu translation)

Such sincerity is a creative force – a key condition of the kind of action called in Chinese wei wuwei – actionless action,….action so focused in harmony with the whole that it creates a perfection far more effective than instrumentally directed technique aimed at some less-than-ultimate end. Cheng, sincerity, is a kind of love for truth, that can bring things beautifully true.

Then let me have a stab at saying what true faith is. Faith is a way of being who we are. It is courage to be sincere about what we are, about our strengths and our flaws, letting them present themselves to us and to the object of our faith – to God. Perfect faith, then, would be utter sincerity about who we are before my God, a sincerity so transparent that we seek no special concession or benefit on the basis of who and what we are– just letting ourselves be in the presence of what ultimately matters. I can’t do this – entrust myself to truth in love – if I am not utterly sincere about myself and equally courageous not to try to change it. And ironically, who and what I am does not matter ultimately. What matters is just that I give myself, as I am, to God, for nothing. Sincere as a bird of the air and courageous as a lily of the field. God will give whatever work comes next.

You can see, I trust, how it is ludicrous to try to reduce faith to a tool or technique for gaining something else. All that faith can give you is yourself. But, then again, it is yourself in the presence of what ultimately matters. So let faith work. Then God will give you work, and God’s yoke will be easy, and the burden light.

So, I believe. Help my unbelief.

Amen.